A landmark agreement was signed by 136 nations allowing for a blanket corporation tax rate to come into effect. Co-ordinated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the two-pillar global tax reform plan is designed to enable a fairer tax system for large multi-national companies particularly technology companies. The global minimum corporate tax rate will be 15% and shall be imposed by 2023.

The OECD, who are based in Paris, reported that only four nations (Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) refused to sign the deal with previous sceptics of the deal (Ireland, Hungary and Estonia) eventually signing up to the agreement. A new taxing legislation will be enforced allowing countries to levy a slice of the profits generated by a handful of the biggest businesses in the world, according to the sales achieved within each nation’s borders.

The global tax floor will only apply to the biggest firms who have annual revenues of €750m. We break down exactly what the landmark OECD agreement is, the implications on the global economy and what the potential further steps could be for global corporation tax.

What Is The Global Minimum Corporate Tax Rate?

The OECD two-pillar global tax reform plan provides a monumental change in corporation tax legislation right across the world. By introducing a global tax floor of 15%, it eliminates the use of tax havens for huge multi-national firms which have notoriously undercut tax payments and affected the economy across the world.

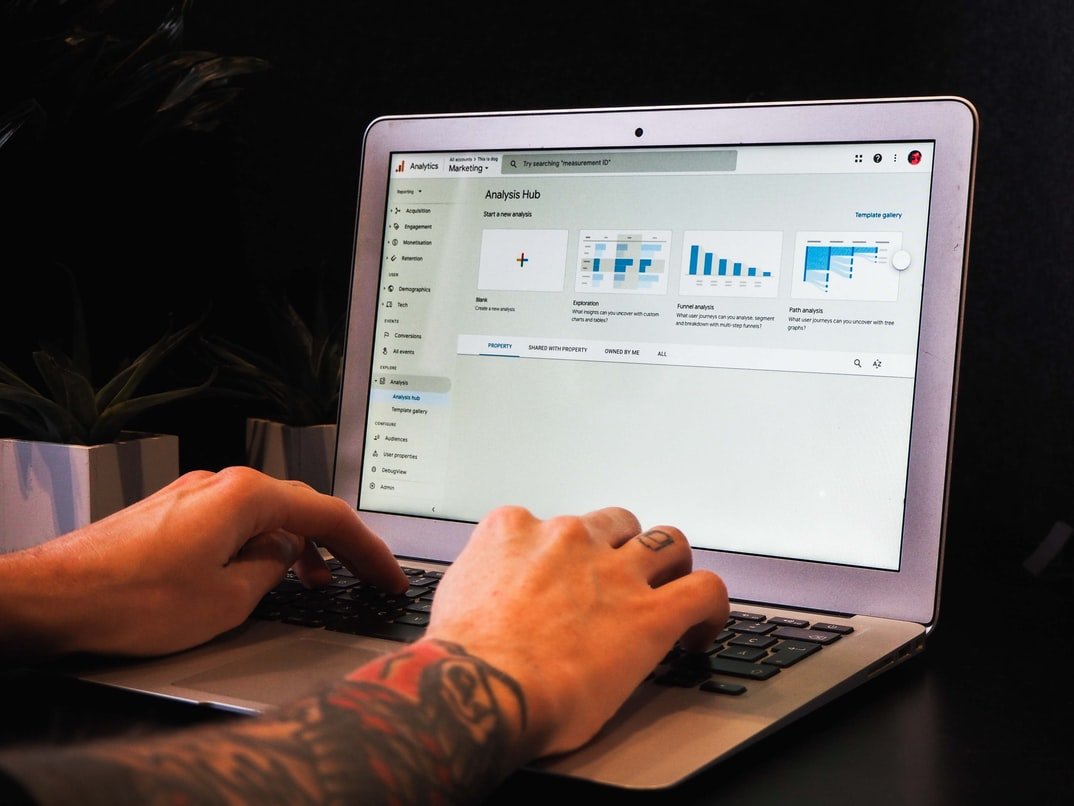

Under the first pillar of the global tax reform plan, it grants the powers for nations levy a slice of multinational organisations’ profits. The OECD have estimated that over than $125bn, equivalent to £92bn, of corporate profits from approximately 100 of the world’s largest multinational businesses would be reimbursed to the respective nations where they do business. The legislation will affect firms with global sales above €20bn (£17bn) and profit margins above 10%. 25% of all profit margins above 10% will be reallocated to the respective nation.

The second pillar of the agreement will set a global corporate tax rate of 15% across the world which will come into effect in 2023. The OECD have estimated that through this second pillar of the measure, it would reallocate an additional $150bn (approximately £110bn) collectively to governments across the world where multinationals do business.

Why Have Hundreds Of Nations Signed Up To The Global Minimum Corporate Tax Rate Legislation?

All 38 OECD members as well as all members of the G20 group have signed up to the landmark agreement. There was initial hesitancy from Ireland who agreed to join after being assured that the 15% corporate tax rate would not be increased further on down the line. Previously, Ireland had a set 12.5% corporate tax rate which was looked upon as favourable from large tech companies including Microsoft, Dell, Intel, IBM, SAP, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, HubSpot and PayPal who all have major presence in the nation.

One of the fundamental reasons that the two-pillar corporate tax agreement was set into place, after a decade of campaigning from the OECD, was due to the stiff tax competition from nations. Nations such as Ireland, Hungary and Estonia, with corporate tax rates below the 15% threshold, were sceptical that they wouldn’t be able to attract foreign investment and large firms doing business. By introducing a unified corporate tax rate it provides stability and transparency for global tax reform that would wholly benefit the worldwide economy.

The UK Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, stated, “the deal would upgrade the global tax system for the modern age. We now have a clear path to a fairer tax system, where large global players pay their fair share wherever they do business”.

What Are The Potential Next Steps For Global Corporate Tax Reform?

Whilst the two-pillar global corporate tax plan has been warmly welcomed by the majority, there are still concerns regarding how effective it will be in holding big companies to account. The corporate tax rate average in industrialised nations is 23.5%, a significant difference to the 15% agreed in the OECD plan.

There are worries that through this legislation, there will be a race to the bottom for wealthy nations looking to cut corporate tax rates. This ‘shop window’ strategy will likely entice big multinational companies to set up base and create jobs, as opposed to doing this in less well-developed nations.

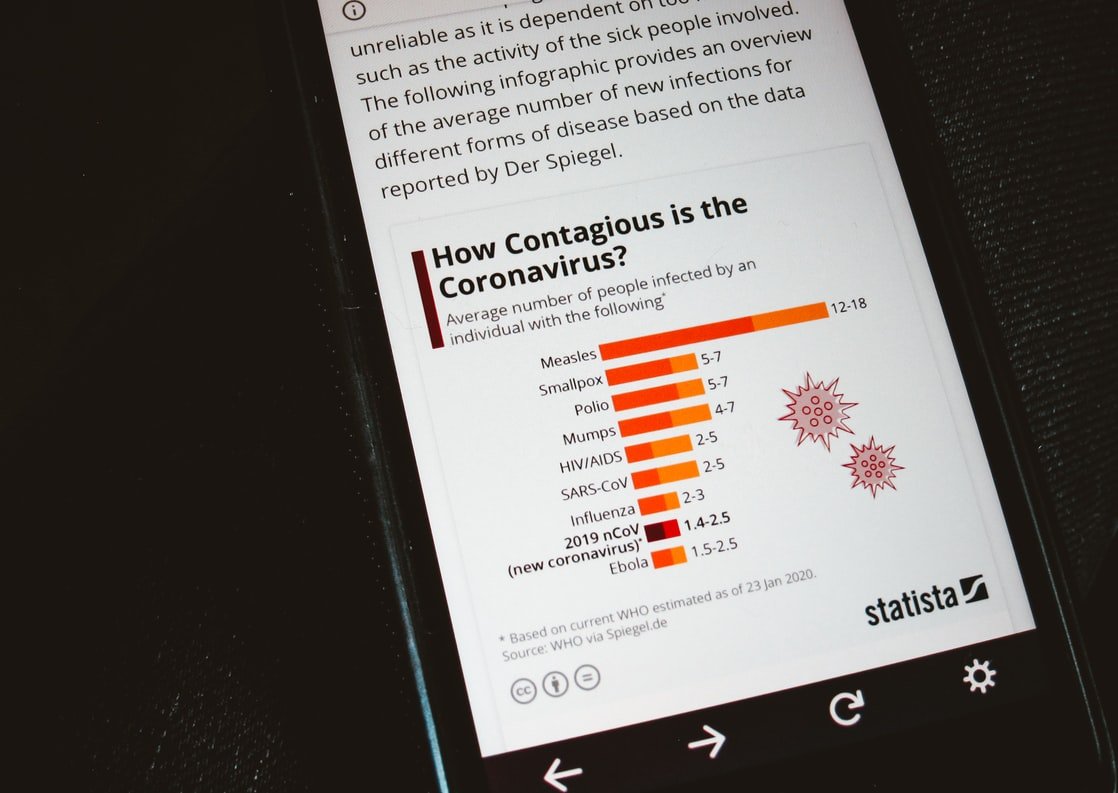

The global inequality, highlighted by COVID-19 and the subsequent vaccine rollout, will possibly persist through the corporation tax tug of war. Due to Ireland having assurances that the 15% would not increase in the future, this negative impact is likely to be experienced come 2023.

We hope this has outlined to you what the new OECD global corporate tax reform plan is and how it will affect the overall global economy. If you require any further information on corporation tax, or anything accounting related for that matter, please don’t hesitate to get in contact with us at Nordens where one of our trusted advisors would be happy talking you through your query.